Soviet Oblivions of Babyn Yar: Anti-Semitism or Cowardice?

"At about 7:30 p.m., the participants of the unauthorised rally dispersed at the instructions of the militia," wrote Communist Party functionary Alexander Botvin in his 1966 report on an unofficial commemorative event at Babyn Yar.

But Israel Kleiner, a participant in a similar event in 1969, described the actions of the police and the KGB in a different way: "The major waved his hands, and the militiamen rushed into the crowd to keep order. They threw the broken, smashed cemetery wreath out of the area, and it fell apart. The secsots [secret informants –TN] pointed their fingers at others and shouted: "Detain this one, comrade sergeant; he is a hooligan!"

The Soviet government suppressed the unofficial memory of the Nazi murder of tens of thousands of Jews at Babyn Yar. Why? It seemed that the entire legitimacy of the Soviet Union was built around the label of "greatness" and the fight against Nazism.

At the same time, this did not prevent the Communist Party from concealing Nazi crimes against Soviet Jews. The results of this policy are still visible today: since the memorial complex was not built during Soviet times, and since Ukraine's independence, there is not enough money for cultural policy, this niche has been filled by a private initiative.

But what were the reasons for this policy?

Stalin's anti-Semitism

Most authoritarian regimes ease their repression when there is an external threat to their existence. They look for allies among their yesterday's victims to survive. Stalinism in World War II is no exception.

There is both quantitative and qualitative proof of this. If at the beginning of the German invasion of the USSR, there were 2.3 million prisoners in the GULAG camps, by 1944, the number was 1.2 million.

It was then that Soviet propagandists relied on controlled nationalism. For example, in 1942, the state publishing house of the Ukrainian SSR published a series of books called Our Great Ancestors about characters in Ukrainian history, from Danylo Halytskyi to Ivan Franko. Similar processes occurred in the Soviet regime's attitude toward Jews.

Soviet Jews organised the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, published a Yiddish-language newspaper, and represented Soviet Jews in international relations. For the state, it was a propaganda tool. For Soviet Jews, however, creating such a committee was an outstanding achievement since other nationalities did not have such organisations.

At the same time, the authorities made every concession and permission only after a series of refusals and objections. After the opening of the Soviet archives, it became known that the organisation was under constant control and criticism from its inception, writes Shimon Redlich, a specialist in East European Jewish history. Eventually, after the war ended, the regime began to refuse concessions.

Filmmaker Solomon Mikhoels headed the committee. In January 1948, a Soviet secret service agent, Vladimir Golubov, encouraged Mikhoels to travel to Minsk. However, the real goal was to assassinate the Jewish playwright. On January 13, the bodies of Mikhoels and Golubov were found near their hotel in the capital of the Belarusian republic. Allegedly, they had been run over by a truck; the true cause of death remains unknown. Mikhoels was buried with honours, and the other members of the committee were repressed.

It was not enough, so the security forces organised another showcase action, the so-called "doctors' case." In 1951-1952, they created an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory. According to it, Jews who worked in elite Soviet hospitals were deliberately poisoning the party leadership. The publication of these statements in state propaganda caused waves of anti-Semitism. However, Stalin soon died, and the campaign was curtailed.

Liberalisation and the Cult of Victory

Under such circumstances, the memorialisation of Babyn Yar was out of the question. However, Khrushchev's liberalisation pushed people of different nationalities to defend their rights. In the case of Jews, the establishment of the State of Israel contributed to this.

But in contrast to these processes, there were others. The Soviet repressive system did not disappear. The security forces continued to try to determine what was permissible in the USSR and what was forbidden. In addition, in the post-Stalin era, the heroic cult of victory in the "great war" began to take shape. In this cult, there is a place for the "unknown soldier," "great commanders," "persistent partisans," and "murdered communists." Yet, these myths cannot provide an answer to the question of why the Germans managed to capture Kyiv.

The confrontation of these trends determined the events of the following decades.

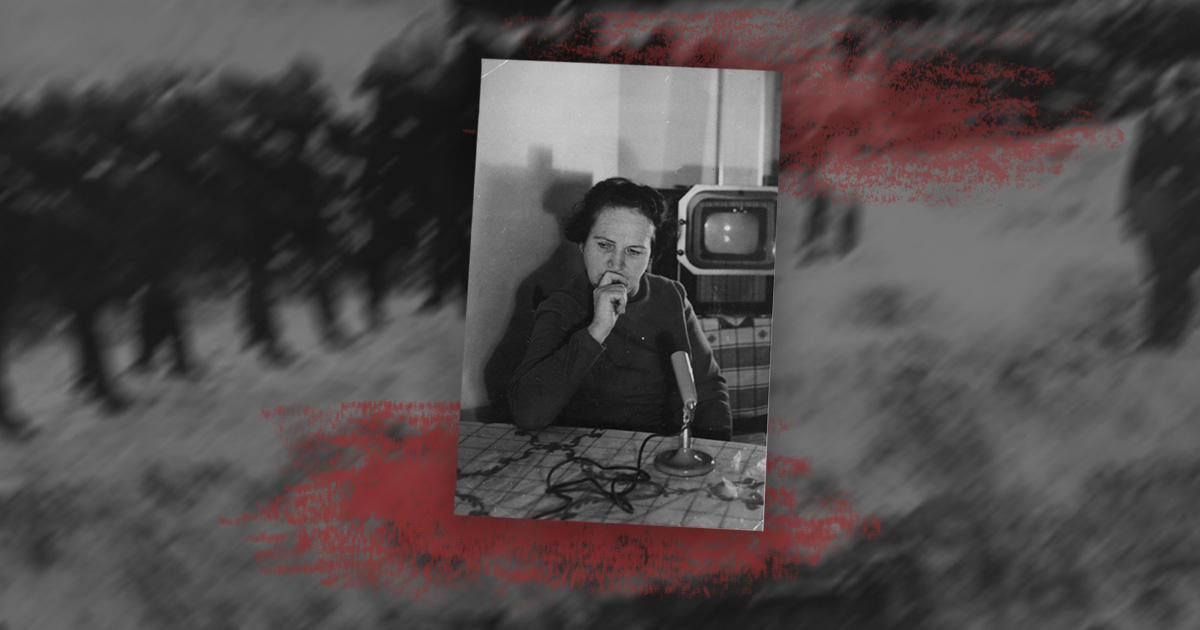

An example is the story of Dinia Pronicheva. On the eve of her execution, she learned of a German order for all Jews to come to the corner of Melnykov and Dehtiarivska streets on September 29, allegedly for resettlement. It was a trap to gather Kyiv Jews in Babyn Yar and shoot them. However, Pronicheva managed to survive and escape. In 1946 she testified about this at a tribunal in Kyiv. Her testimony was filmed, but later the recording disappeared. Finally, in the sixties, she spoke again about what she had seen, but there was no evidence left this time either.

At the same time, the Soviet government tried to create its ritual of memory. Here is how Israel Kleiner describes it: "Every year on this day [September 29 — ed.n.], an official rally is held in the ravine under the auspices of the KGB. It always takes place during working hours and starts at a different time every year, and this time is kept secret. This way, they avoid large crowds."

Plainclothes officers and party activists from neighbouring factories attended the meeting. They laid several wreaths dedicated to "fallen Soviet citizens"-without mentioning that the victims were mostly Jews.

Official rallies took place during working hours, making it impossible for "outsiders" to participate. Instead, unofficial ones took place in the evening near the "stone," an obelisk erected in 1966.

Even the monument's appearance to the "victims of fascism" was caused by non-state activity. On the 25th anniversary of the shootings in the ravine, a sizeable unofficial action took place. Jewish activists, Ukrainian activist Ivan Dziuba, and Soviet dissident Viktor Nekrasov attended it. After that, the party felt the need to seize the initiative.

This is how the "stone" appeared. Now there is a monument in its place, erected in 1976. But it is no better because it is dedicated to "Soviet citizens and prisoners of war, soldiers and officers of the Soviet army who the German fascists shot in Babyn Yar." Not a word about Jews.

Only the collapse of the USSR made it possible to commemorate one of the most important sites of the Holocaust.

Reasons for forgetfulness

There are dozens of explanations for why the Soviet Babyn Yar was the place where anonymous "Soviet citizens" were killed. For example, it was influenced by the Arab-Israeli conflict. In 1967, after the outbreak of the Six-Day War, the USSR broke diplomatic relations with Israel.

In addition, the party was afraid of any opposition: general democratic, Ukrainian, Russian, and thus Jewish. It is also understandable that the party leadership was trampled by the first year of the Nazi invasion and was afraid of anything that reminded them of this defeat. But this does not change the fact that the Communists covered up the Nazi crimes.

The Germans did not kill only Jews at Babyn Yar, but this argument led to the relativisation of the Holocaust. Everyone shot deserves to be remembered. It is reflected in the landscape of the ravine today: there are memorials to Jews, Ukrainian nationalists killed, Roma, prisoners of war, and patients of a mental hospital.

However, this diversity should not distract from the fact that Jews were the main target of the Nazis. And Soviet oblivions should serve as a lesson: we must recognise all pages of our history, both pleasant and traumatic.