Austria: Imposed Neutrality of the Former Empire

The Economist recently included Austria in the list of countries whose political leadership served as "useful idiots" for the Kremlin. There is plenty of evidence to support this thesis. For example, Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer was one of the first European politicians to travel to Russia after the start of the full-scale invasion. He claimed this was not a friendly visit; instead, he wanted to convince Putin to stop the war.

"I think it's important to do something," Nehammer said. However, in the end, this trip had only one result - Austria recognised the idea of travelling to Russia as acceptable.

However, such views and behaviour are typical for the country's political leadership and voters. For example, 53% of Austrians believe that Russia's invasion of Ukraine poses a threat to them. At the same time, the average level of this indicator in the EU is 75%. The Austrians are the second lowest. Only Cypriots are less likely to think so.

In addition, in February 2023, 65% of Austrians were convinced that Ukraine should stop defending itself and start peace talks. This opinion was popular among voters of all political parties except Grüne Alternative (Grüne Alternative).

How did it happen that there is an island of pro-Russian views in the centre of Europe? And how will this country's policy towards Ukraine develop in the future?

From Empire to First Victim

On the eve of the First World War, the Austro-Hungarian Empire covered the territory from the Czech-German border in the north to the Montenegrin coast of the Adriatic Sea in the south, from the border with Switzerland in the west to the modern Ternopil region in the east.

The defeat in the First World War, the mobilisation of Central and Eastern European peoples, and the spread of social democratic ideas led to the Empire's demise. Hungary, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia), Czechoslovakia and the Western Ukrainian People's Republic, quickly occupied by Poland, emerged on its territory. In addition, Romania expanded its borders by gaining the southeastern regions of the empire. Without all these territories, the empire became impossible, so the republic was established in those areas where the population spoke German. Austrians often call this state the "first republic".

Its political life hardly differed from that of most of its neighbours. It was a time of high unemployment, radicalisation, and opposing poles. This confrontation occurred not only in the Parliament but also in the streets, between nationalists and social democrats.

In Austria, this was also complicated by the fact that the Austrian identity was not yet established. In 1918, the republic was proclaimed "Deutschösterreich" (German Austria). However, during the peace negotiations in 1919, the winners forced Germany and Austria to promise never to unite into one state. Such a union would have upset the balance of power created during the peace negotiations to limit Germany's capabilities.

Many Austrians felt more loyal to their former monarchs, the House of Habsburg-Lorraine than the republic. For this reason, in 1919, the government approved a law that banned members of the dynasty from the country, except for those members of the imperial family who had publicly renounced their desire for state power.

However, while the Habsburgs could simply be expelled from the country, thereby limiting Austrians' loyalty to the imperial past, controlling loyalty to German identity was more difficult. Therefore, when the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, and it became clear that Adolf Hitler would seek unification with Austria despite the prohibition, Austrian nationalists began to act sharply.

The conservative chancellor at the time, Engelbert Dollfuß, took advantage of the crisis in parliament and dissolved it. He seized all power and began to develop his ideology of Austrofascism. However, in 1934, Austrian supporters of German Nazism assassinated Dollfuß and attempted to seize power. The fascist leader of Italy, Benito Mussolini, came out in favour of the Austrian regime. Adolf Hitler, unwilling to lose his most important ally, abandoned his plans to seize power and distanced himself from the coup plotters in every way possible.

Mussolini had the advantage in the Germany-Italy pairing then, but the situation changed in four years. In 1938, the Nazis invaded Austria through diplomatic pressure and threats to use the army. There were indeed plans for an invasion, but they did not come to fruition — the Austrian leadership agreed to the ultimatum, and the Austrian population welcomed the entry of German troops and Hitler personally. In March 1938, he did what Putin failed to do in February 2022. The analogy is deepened because even the Austrian dictator Dollfuß called Germany "big brother".

In this way, the Nazis finally destroyed the already weakened system of international relations built up by the peace agreements after the First World War.

Therefore, when the Allies began to think about how to rebuild this system during the Second World War, Austria was one of the first issues to come up. The United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union discussed it at a conference in Moscow in 1943. As a result of the meeting, the trio adopted a declaration that Austria was "the first victim of Hitler's aggression". Therefore, after the war, the country was to become independent again.

Initially, this concept was promoted by the United Kingdom; the Soviet Union insisted that the Austrians' involvement in Nazi crimes should not be forgotten. Later, however, Joseph Stalin also adopted the model of whitewashing people from Austria. It got to the point that a month later, at a conference in Tehran, Joseph Stalin stated: "All German soldiers fight like devils; the Austrians are the only exception". This thesis is not supported by any evidence and is excluded from the Soviet report on the conference.

However, it demonstrates the approach that the USSR would sell in its relations with Austria in the following years: the Austrians are similar to the Germans, still separate and better.

From "unchanging neutrality" to the European Union

Therefore, after the end of the Second World War with the Allies' victory, the Soviet Union's approach to Austria demonstrated both similarities and differences to the occupation regime in Germany. First, Austria, like Germany, was divided into occupation zones. While in Germany, the proclamation of states based on these occupation zones took until 1949, in Austria, it happened almost immediately after the arrival of Soviet troops.

Stalin accepted Winston Churchill's proposal for Austrian independence for a reason. The USSR hoped to establish a loyal regime in Austria. However, this did not happen: in the autumn of 1945, the first elections to the Austrian parliament were held, in which the Communist Party won only 5%. The Communists had seats in the first provisional government that ran the country before the elections and the second full-fledged government that ran the country afterwards. However, after the next elections in 1949, the Communist Party of Austria went into opposition, receiving the same 5%.

In addition, Austria cooperated with the United States. It joined the European Recovery Programme (known as the Marshall Plan), which aimed at helping to rebuild Europe and prevent the spread of communism. No other country with Soviet troops on its territory could join the plan because of Soviet opposition. Understanding this feature, the United States made special efforts to fund Austria, which resulted in the country's third-highest per capita international aid.

But the Kremlin could still twist the arms of all the other parties in Austria's return to independence — the United States, Britain, France, and Austria. The Union Council, which included a Soviet representative, could veto any law but, in practice, had little influence. However, Soviet troops were still stationed in Austria, which created a constant sense of uncertainty. The country remained an incomplete state without its army.

Moscow played a complex diplomatic game around the Austrian issue, culminating in the Berlin Conference of 1954, where the foreign ministers of the United States, Britain, France, and the USSR met. The Kremlin's motivation was both political and financial.

Political motivation. The USSR tried to link the German and Austrian issues. The head of Soviet diplomacy, Vyacheslav Molotov, said that the USSR could not withdraw from Austria until a peace treaty was signed between the Allies and Germany. But such a treaty could not be concluded because Germany did not exist as a single state. So how to achieve unification?

The United States, Great Britain, and France delegations noted that the Soviet Union refused to hold free and democratic elections in its occupation zone. If they succumbed to the Kremlin's provocations and took the first step by withdrawing their troops, Moscow would quickly devise a pretext to invade all of Germany. To combine this framework with the discussion about Austria, Soviet propaganda artificially stirred up panic that West Germany was planning to re-annexe Austria.

A typical article promoting this thesis used evidence that Austria was increasing electricity supplies to its northern neighbour. It is difficult to see how this suggests plans to take over Austria. Nor is it possible to imagine how West Germany was supposed to invade anyone since it had no army of its own as of 1954. The United States, Britain, and France did not respond to Soviet manoeuvres, so the Berlin Conference ended in nothing.

Economic motivation. At the same Berlin conference, Molotov also mentioned another issue to resolve before they withdrew troops from Austria. Austria was not obliged to pay reparations, as it was considered the "first victim". However, there were so-called "external German assets" on its territory, i.e. industrial property owned by Nazi Germany outside its post-war borders. According to the decisions of the Potsdam Conference of 1945, the Allies were to receive reparations from these assets. Therefore, the USSR demanded that Austria either hand over this property or pay its cost. Until a solution was found, the Kremlin continued to make money from this property, managing it from the occupation zone.

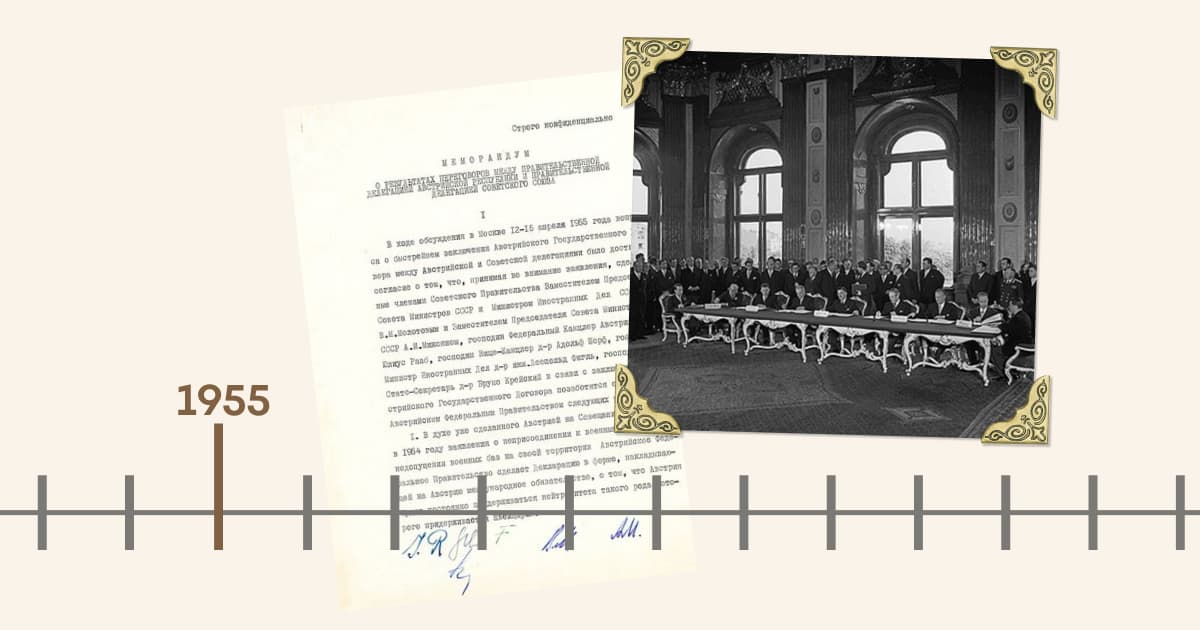

But soon, a solution did emerge. And the circumstances under which it emerged once again confirm the manipulative nature of the Soviet position. In 1955, West Germany joined NATO and began building its army. Following the Kremlin's logic of last year, it would have increased the threat of further Austrian accession. But in reality, Moscow was interested in something entirely different.

During the Berlin conference, Austria declared its readiness to declare neutrality. This proposal looked more interesting, as it would create a wall of neutral countries, such as Switzerland and Austria, between West Germany and Italy. This would have slowed the transfer of troops between the two NATO members. And there was no room to postpone this issue any longer, as ten years had passed since the end of the war.

In February-March, West Germany ratified the Paris Agreement on the de-occupation of the country, which also provided for NATO membership. As early as April, the Austrian delegation in Moscow signed a memorandum stating that "Austria will always maintain neutrality of the kind maintained by Switzerland". Only then was the signing of the de-occupation treaty between Austria and the Allies unblocked. It was approved in May 1955.

Even though the USSR had drained the country of its resources, Austria did not deteriorate its relations with the Soviet Union after gaining independence. On the contrary, it cooperated with the USSR and the United States. The leaders of the Cold War rivals, including John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev, held talks in Vienna. Jimmy Carter and Leonid Brezhnev signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty.

Nevertheless, relations with the USSR were not rosy for Austria. The country could not join the European Economic Community for fear of a backlash from Moscow. This limited the country's economic growth. Only the collapse of the USSR allowed Austria to join.

The present: Ibiza, trade and a weird neutrality

Before joining the EU, the Austrian economy was not integrated into the global economy. Austria pursued a somewhat autonomous economic policy. The state encouraged businesses to keep unemployment rates to a minimum. This is a trauma of the "first republic", where unemployment led to a sharp confrontation between political and social groups. There was little foreign capital in Austria during the Cold War. Over 80% of Austrians worked for small and medium-sized enterprises, and hardly any Austrian transnational corporations existed.

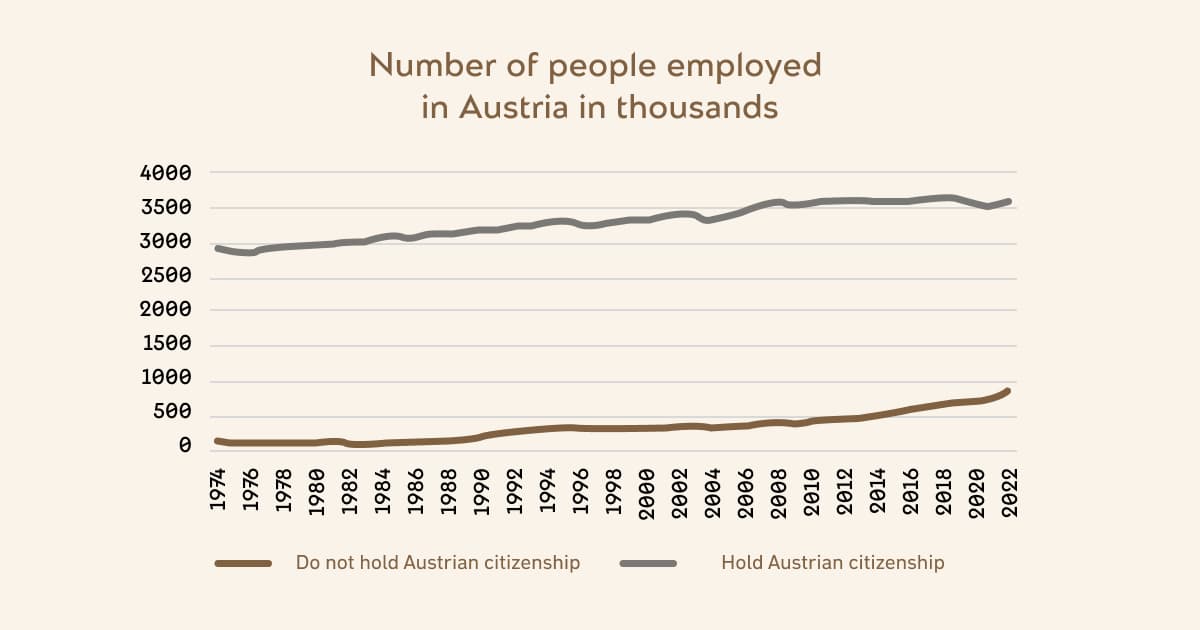

Now everything looks different. If only Austrian citizens go to work in Vienna tomorrow, they will most likely not be able to get to their jobs, as 51% of those employed are foreigners. This figure is lower across the country: in 2022, it was 23%. However, it is growing every year. Between 1974 and 2022, the number of employed Austrians increased by around 20%, while employed foreigners increased by over 400%. However, in absolute terms, this growth is almost identical for both groups: 668,000 to 688,000.

A large proportion of foreigners are EU citizens who have privileged access to the labour market. At the same time, one should not forget that not all Austrian citizens have Austrian ancestors. There may be people born in Austria but whose ancestors originated in Turkey, the former Yugoslavia or Syria. The number of people in the country who are not ethnically Austrian is multiplying.

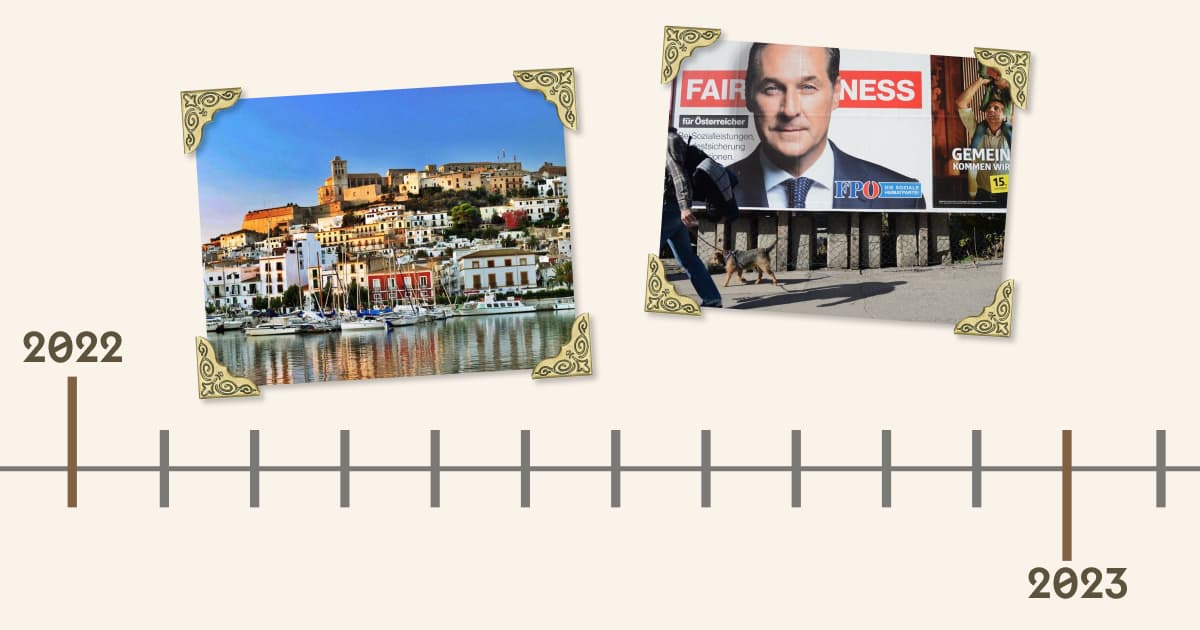

The success of the Freedom Party of Austria (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs) in the 2017 elections is linked to the manipulation of this topic. It is a far-right party that, together with the People's Party and the Social Democratic Party, is one of the country's three significant political forces. Currently, it is the most pro-Russian, although 25 years ago, it advocated Austria's accession to NATO despite its neutrality. However, after a brief rise in its ratings at the beginning of the 21st century, it has returned to third place in popularity.

The 2017 elections were a breakthrough for the Freedom Party not only because of the increased number of refugees due to the war in Syria. The party's leader played a crucial role at the time, Heinz-Christian Strache, who gained popularity due to his unconventional leadership style.

He led a peculiar lifestyle for a national politician: constant parties, nightly tours of Viennese clubs and mixing vodka with Red Bull. He even had a separate fridge for his energy drink. Strache was where the young people were winning their votes. He also attracted the support of the Russian Federation — in 2016, his party signed a cooperation agreement with Yedinaya Rossiya (United Russia). Strache's party won 25% of the vote the following year, so the conservative People's Party formed a coalition with the far right. Strache was appointed vice-chancellor.

However, on the eve of the election, something unexpected happened. Strache's bodyguard, Oliver Ribarich, was tired of the nightlife financed by the party budget. In addition, he saw that his boss started carrying large amounts of cash in bags. So the man turned to a lawyer friend for help, and he, in turn, turned to private investigator Julian Hessenthaler. His task was to remove Strache from power before he did anything else.

The detective knew Strache's righthand man, party functionary Johan Gudenus, was interested in money and Russia. Gudenus is so loyal to Putin's regime that he has even travelled to Chechnya to see Kadyrov and the temporarily occupied Qirim. So Hessenthaler decided to get to Strache through Gudenus, offering him alleged cooperation with the Russian oligarch.

For this purpose, the detective hired an employee who pretended to be the oligarch's daughter. Hessenthaler rented a villa in Ibiza and obtained special cameras for secret filming. The "oligarch's daughter" invited Strache and Goodenus to the mansion to discuss the deal's details. In the video, Strache is seen drinking energy drinks, responding positively to the bribe offer, and planning to buy an Austrian media outlet with Russian money.

The detective was unable to publish the video quickly. He did not release it to the media until 2019, when the government collapsed and Strache lost power and resigned from the party. However, this did not make the Freedom Party members any less pro-Russian or Austrian society.

Currently, the Freedom Party is ranked first in the polls. It enjoys the support of 28-30% of the population. It is a record high, as this political force has never managed to win so many votes in an election before. The far-right party is opposed to providing aid to Ukraine. When the President of Ukraine spoke in parliament, members of this party walked out of the room. It was allegedly explained by a desire not to violate their "unchanging neutrality". Far-right politicians oppose sanctions and claim that such measures harm the Austrian economy.

However, statistics show otherwise. In 2022, exports of Austrian goods to Russia did not fall but reached record levels — Austrians sold their products for €7 billion. It proves that when it becomes difficult for Russians to work with Europeans, they turn to a country that accepts the Russian position. As of 2023, the effect of the sanctions has become more noticeable, and sales have dropped, but it is too early to draw general conclusions.

In addition, the Freedom Party criticises using Austrian EU membership fees to buy shells for Ukraine. This fact is not surprising, but it demonstrates the dubiousness of Austria's neutrality. After the country joined the European Union and assumed foreign policy responsibilities, the space for Austrian manoeuvres shrank. Can a country be genuinely neutral when it is a member of an alliance that promotes specific values? The Austrians continue to answer this question positively, but as international relations become more tense every year, it becomes more difficult.

But in addition to making it increasingly difficult for Austria to conduct foreign policy, neutrality is also a convenient cover for supporting Russia. In 2024, the country will hold elections. If the Freedom Party comes to power, it will use this as a cover to try to destroy European sanctions and aid for Ukraine. Austria and Hungary will reunite again, not as a single state, but in a joint effort to block or delay any EU decision.

Ukraine has no right or means to influence the domestic political situation in Austria. Therefore, it is up to the Austrians to decide: do they want to live in a society filled with hatred for non-white people and in a country that cooperates with Russia and is indirectly responsible for the dead Ukrainians?