Democracy is a process: How Georgia changed its course

Back in 2014, the media said that Georgia should be an example for post-Soviet countries, given its struggle for transparency in law enforcement, stability of state institutions and pro-European course.

After Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Georgian government refused to impose sanctions on Russia and allowed Russian planes and tourists to visit, even though Georgians support Ukraine.

In this article, we explain why reforms in Georgia have come to a standstill, why the country is turning towards Russia, and what mistakes Ukraine should not repeat.

When the reform process in Georgia came to a standstill

In October 2012, the Georgian Dream party (ქართული ოცნება) came to power in Georgia. It was founded by Georgian businessman Bidzina Ivanishvili. He is considered the wealthiest man in Georgia — in 2023, his fortune was $4.9 billion.

The party positions itself as pro-European, supporting Georgia's territorial integrity and integration into NATO. Similar points were also in the United Nations Movement programme of former Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili. However, the Georgian Dream also promised a pragmatic policy towards Russia regarding trade and tourism between the two countries, which was a decisive factor for Georgians in 2012. The United National Movement went into opposition, and Saakashvili left Georgia for a while to become a Ukrainian politician.

Political analyst Nino Samkhradze, a PhD student at Tbilisi State University's Department of Political Science, describes the Georgian Dream as a right-wing, populist-conservative party. In her words, the party is “focused on staying in power, even at the risk of legitimising the democratic process”. The party reinforces conservative, emotional or conspiratorial narratives to mobilise and strengthen public support.

“The United National Movement is committed to a policy of economic liberalisation, expanding social support programmes for vulnerable groups and transitioning to conscription.

Bidzina Ivanishvili is a significant figure for the Georgian Dream. He moved to Moscow in the 1980s, where he quickly made a career in the banking sector. In 1996, Ivanishvili sponsored Russian General Alexander Lebed's campaign to siphon votes from the Communist Party and help Boris Yeltsin win the presidential election — Ivanishvili's first attempt to influence politics.

He was criticised in Georgia for this decision. Lebed was one of the generals who led the crackdown on pro-Georgian protests in Tbilisi in April 1989. At the time, the Soviet military officially killed 19 demonstrators.

Ivanishvili explained his decision: “During Yeltsin's election, there was an excellent opportunity for the Communists to make a comeback. Lebed could best balance the Communists. In the end, it was my position that led to Boris Yeltsin's victory and prevented Georgia from going backwards.

In 2003, Ivanishvili returned to Georgia from Russia and again tried to influence the political situation by financially supporting the Rose Revolution, a mass protest against President Eduard Shevardnadze. The result was the government's resignation and the election of Mikheil Saakashvili as president. Nine years later, Bidzina Ivanishvili led Saakashvili's opposition party into parliamentary elections.

After the 2012 elections, Ivanishvili became the country's prime minister but resigned a year later, announcing that he was “retiring from politics”. This decision was attributed to the election of Georgian Dream candidate Giorgi Margvelashvili as president in 2013, as the party was able to take over the country's leading governing institutions. In a year, Ivanishvili has liberalised the penitentiary system, passing an amnesty law that halved the number of prisoners. He also reformed the health system and expanded publicly funded health services.

Georgia continued to move closer to the EU. The government and the European Commission began negotiations on the visa regime and trade relations.

Relations with Russia have also warmed. In December 2012, both governments met for the first time in Prague, the capital of the Czech Republic, when Georgia unilaterally cancelled the visa regime for Russian citizens. It took 11 years to get a reciprocal step.

“Since winning the election in 2012, the Georgian Dream has been trying to partially reset relations with Russia: Georgia sought rapprochement in the economic and cultural spheres while maintaining the status quo in military and political relations. The result was establishing a dialogue between the countries on economic and cultural issues. At the same time, political and security relations remained the same as before,”

Irakli Sirbiladze, a Georgian political analyst and ReThink.CEE Fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States told Svidomi.

Georgians and the current government

The Georgian Dream won the 2020 parliamentary elections with over 48% of the vote for the third time. However, according to the opposition, the turnout was relatively low.

“There are many polling stations where the Georgian Dream received over 300 votes, but the turnout was 50, 60 or less than 70 people. It's all on record,” said Mikheil Saakashvili, leader of the United National Movement, in 2020. At the time, almost 57% of all voters in Georgia took part in the elections, which is 5% more than in 2016.

“The reasons for the victories of the Georgian Dream include the ruling party's retention of the so-called administrative resource, excessive financial resources compared to other political parties, and the inability of the opposition to renew itself and present itself as a credible alternative to the ruling party,” says Irakli Sirbiladze.

According to a survey by the International Republican Institute, in 2022, over 70% of Georgians want to see the country become an EU member; 90% of the country's residents view Russia as a threat.

The 'Georgian Dream' still declares a course towards European integration, but fewer citizens believe it. The ruling party is supported by 30%, and this support is falling.

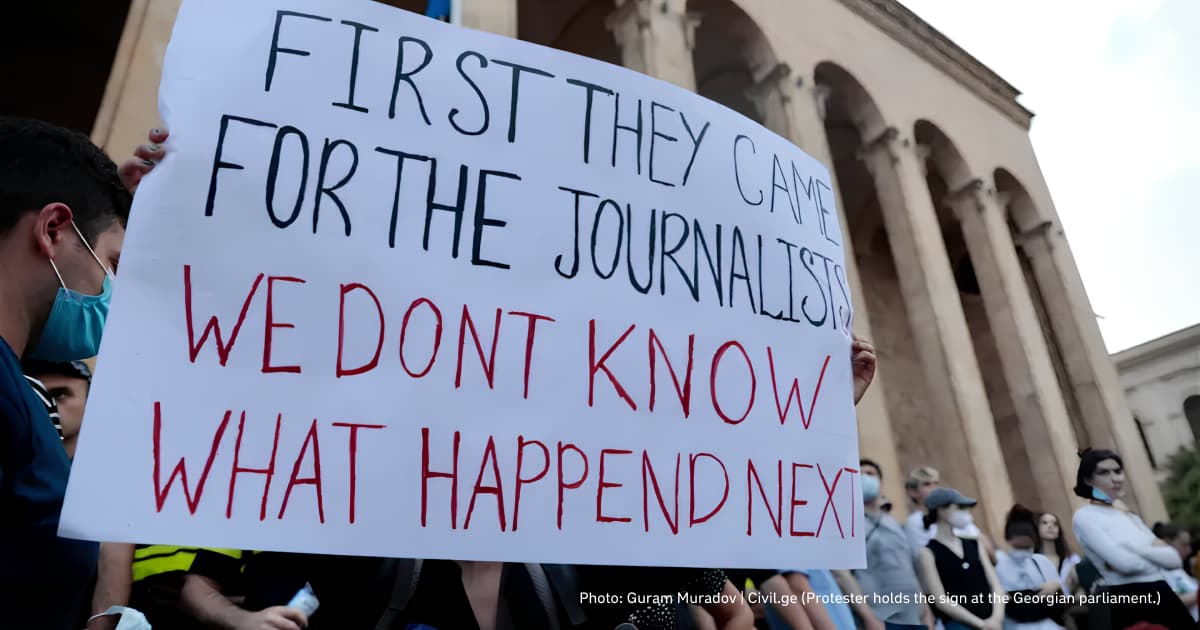

Georgian activists tell about a 'semi-authoritarian regime' established in the country. This is evidenced by the decline in press freedom ranking in the World Press Freedom Index — from 60th place in 2021 to 89th in 2022. Reporters Without Borders said that “intelligence services wiretap influential public figures in the country, violating the confidentiality of journalistic sources”.

Georgian society is polarised. According to a survey by the National Democratic Institute, most of the country's citizens believe it is divided by different forces, including 87% of politicians and 79% of other leaders.

According to the Georgian Institute of Politics, polarisation in the country is created by the most significant political parties — the ruling Georgian Dream and the opposition United National Movement. The polarisation has no ideological basis, and the parties use radical rhetoric to influence Georgian society.

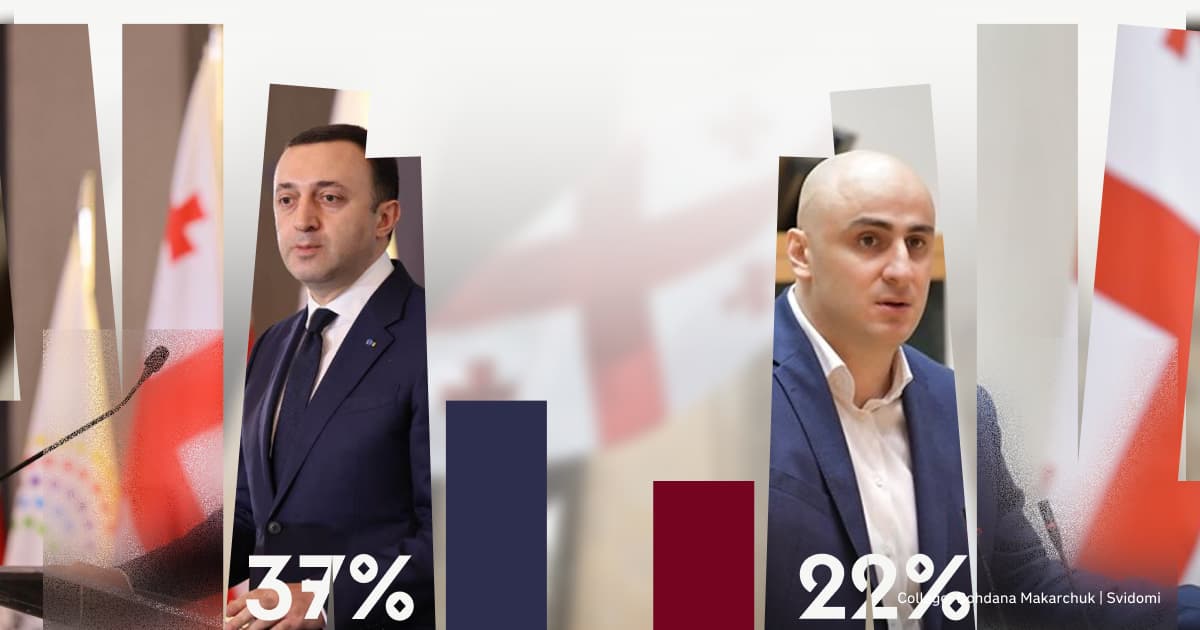

In 2024, Georgia will hold parliamentary elections. According to an Edison Research survey, 37% of respondents are ready to vote for the Georgian Dream. This is 11% less than in the 2020 elections, but such a result would still bring the party victory. “The United National Movement has the support of 22% of respondents.

“Opinion polls show that, compared to other political parties, the Georgian Dream is still the preferred option for the citizens of Georgia. However, in hybrid regimes (regimes that combine democratic institutions, such as suffrage, with authoritarian ones, such as repression of political opponents — ed.), like Georgia, opinion polls are rarely a reliable indicator of election results,” says Irakli Sirbiladze.

Russia's war against Ukraine and the consideration of Georgia's EU membership application are new factors for the Georgian Dream in the 2024 parliamentary elections, Sirbiladze says. The ruling party enjoys administrative resources and has financial assets compared to the opposition. But, according to the expert, the opposition can mobilise voters if it forms the correct agenda.

“The main request of the Georgians in the elections is to improve the economy. This is the main reason for their desire for EU membership. The Georgians believe that integration into the EU will stimulate the country's economy and give citizens more protection from the government's increasing authoritarianism.

However, Megi Kartsivadze, a PhD student at the University of Oxford, is sceptical about the ability of the opposition in Georgia to turn the political situation in their favour. She believes that the opposition media is controlled by people who are interested in polarising society.

“This leaves almost no room for other smaller parties or new political faces to emerge and establish themselves as key players in the current political situation,” Megi Kartsivadze told Svidomi.

Georgia after the start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine

According to the US State Department, by 2023, about 20% of Georgia's territory will be occupied by Russia — Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Russia is actively integrating the occupied territories into its system, spreading its propaganda and moving the line of occupation deeper into Tbilisi-controlled territory.

Despite this, Georgia is actively trading with Russia. In 2019, the share of Georgian exports to Russia averaged over 13% of the country's total exports. Russian tourists account for nearly 16% of all tourists in the country.

After Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Georgia became one of the main destinations for Russian emigration. At the end of 2022, Russians were the first foreigners to immigrate to the country in one year. The State Statistics Service puts the figure at more than 60,000 immigrants. Still, Georgian media believe the number of Russians could be higher due to the visa-free regime and unwillingness to legalise.

“For many years, Georgian Dream has claimed to be the only ruling party that has avoided direct war with Russia. They justify their rapprochement with Russia by emphasising peace and stability — something that may appeal to a public that has seen the horrors of war (Russian troops attacked Georgia in 2008 – ed),” says analyst Irakli Sirbiladze.

But the situation is worse with sanctions against Russia and condemnation of aggression against Ukraine. On February 25, 2022, the Prime Minister of Georgia, Irakli Garibashvili, said that the government would not impose sanctions against Russia as it would “harm the economy of Georgia”.

Irakli Sirbiladze explains that the Georgian Dream fears the closure of the Russian market for Georgian products, which will have economic and electoral consequences for the party.

“By seeking economic relations with Russia, the Georgian Dream has fallen into economic dependence,” he says.

The National Bank of Georgia announced that it would enforce sanctions against the Russian bank VTB, which has a branch in the country, thus limiting transfers in dollars, euros and other currencies. At the same time, the bank added that "in case of need for additional liquidity, the National Bank of Georgia is ready to provide the bank with appropriate financial resources".

In 2023, the Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs reported that Georgia was helping Russia to circumvent sanctions. The volume of Georgia's trade with Russia has grown the most of all neighbouring countries due to the so-called parallel imports — by almost 22%. Most of these are consumer goods, but they are also dual-use goods such as microchips that can be used in the military industry.

Russia's support has already affected Georgia's relations with the European Union. The European Commission sees the country as a potential EU member, but in 2022, the Council of the European Union denied Georgia candidate status (the country received candidate status only on December 14, 2023 - ed.).

The Council has set 12 conditions for EU candidate status, but the Georgian government has been slow to implement the requirements of its legislation. As of October 2023, the country has met three conditions: it has implemented a gender equality policy, appointed an independent human rights ombudsman, and complied with the European Court of Human Rights rulings.

The Georgian parliament is also trying to introduce laws similar to those in Russia. For example, in the spring of 2023, a bill was submitted for consideration requiring organisations and media to declare themselves as 'foreign agents' if more than 20% of their budget came from another country. Georgians protested against the bill, so it was withdrawn. It is now 'suspended'.

In 2024, Irakli Garibashvili resigned as Prime Minister of Georgia and became leader of the ruling Georgian Dream party. The new prime minister was Irakli Kobakhidze, a former speaker of the Georgian parliament. As a speaker, Kobakhidze cooperated with pro-Russian organisations such as the Interparliamentary Assembly on Orthodoxy (in 2023, Ukraine appealed to the organisation to condemn Russia's invasion of Ukraine; Russia is still an active member of the assembly – ed).

“The ruling party is becoming increasingly authoritarian, learning from Russia's practice of silencing the opposition, civil society and media that criticise the government. Their narratives constantly stress the danger of involving Georgia in a war, appealing to emotions and presenting themselves as guardians of peace. "The Georgian Dream is trying to interpret geopolitical events, and Russia's war against Ukraine in such a way as to convince people that voting for them means stability and no war, and voting for the opposition means war with Russia,”

explains analyst Sirbiladze.

Megi Kartsivadze thinks the same. She says that the Georgian Dream is deliberately polarising Georgian society. At the same time, the United National Movement opposes itself as the only alternative to the Georgian Dream. The polarised environment keeps Georgian society “in a kind of toxic loop” used by both the ruling party and the opposition.

The current government's behaviour proves that democracy is a process, and it is easy to go back to square one and roll back all reforms and progress.