What was the Kherson region's reaction and response to the occupation of Crimea in 2014?

In February-March 2014, Russia illegally occupied Crimea (Qırım). At that time, the Russian military also crossed the administrative border of the Kherson region, seized part of the Arabat Spit (Arabat beli), landed on the Ad Peninsula, and gained a foothold on the Chonhar Peninsula (Çonğar).

Russia controlled these areas from March to December 2014, then withdrew. In 2022, the Kherson region was one of the first to be almost completely occupied by Russia. The Russian army still controls the left bank of the region.

Read the article to learn how the Kherson region prepared or did not prepare for a possible escalation after the occupation of Crimea in 2014.

How it all began

In March 2014, Kherson journalist Ivan Antypenko travelled with volunteers to the administrative border with the Crimean peninsula. Later, the so-called "entry-exit checkpoints" appeared there.

"Until then, there were simple checkpoints with police and border guards. We saw the first Ukrainian military equipment. [Ukraine] was trying to strengthen the line," Antypenko told Svidomi.

In his words, the Ukrainian military sent to the border looked inappropriate. "It was different from the army we see now," the journalist says.

"At the same time, the soldiers said that they were treated very kindly and with support by the residents of the Kherson region, who began to bring them food and other stuff," Ivan Antypenko recalls the military's words.

The journalist adds that, in his opinion, not everyone in the Kherson region fully understood the threat coming from the Crimean peninsula.

"With time passing and no events happening there, it is obvious that the military realized that sooner or later this direction would break through. But according to my observations, there was no tension in 2019-2020 compared to 2014-2015," Antypenko adds.

Preparing shelters and emergency alert systems

"[The occupation of Crimea] was seen as a temporary phenomenon. No one believed that it could turn into what we are seeing now. There were checkpoints [between Crimea and the Kherson region], and that was it," Yevhen Yuldashev, former deputy head of the Beryslav district state administration, tells Svidomi.

Recalling the first days of Russia's occupation of the peninsula, he says he realized what had happened after the illegal pseudo-referendum on the peninsula.

At that time, Russia "announced" that the population of Crimea had allegedly voted in favour of annexation. Ukraine's Constitutional Court declared the Crimean parliament's decision to hold the referendum unconstitutional.

Preparing shelters or civil defence facilities was one of the first tasks assigned to local administrations after Russia's illegal annexation of Crimea.

The regional state administration's Department of Housing and Communal Services and Emergency Situations was responsible for the inventory, as the order of the head of the Beryslav district state administration dated February 24, 2014, states.

According to the document, the main tasks of the inspection were to update the electronic database of civil protection facilities and to ventilate shelters in municipal and private ownership.

"Once these facilities were accounted for, but after independence, this accounting was lost. In fact, no one really dealt with this issue because, according to the law, the owners of civil defence structures were responsible for the condition of their facilities. After 2014 a commission was established. The inventory was carried out only in the buildings of budgetary institutions," says the former deputy head of the Beryslav District State Administration.

There were no significant changes after the inventory. According to Yuldashev, some cosmetic repairs could have been made, chairs could have been arranged, etc., but there was no question of re-equipment.

All these things were provided for earlier, but over time the shelters were abandoned and adapted as utility rooms or storerooms [until 2014 — ed.]. There was open access to them, but in most cases, these shelters, which could be adapted as bomb shelters, were not ready,

says the former deputy head of the Beryslav district state administration.

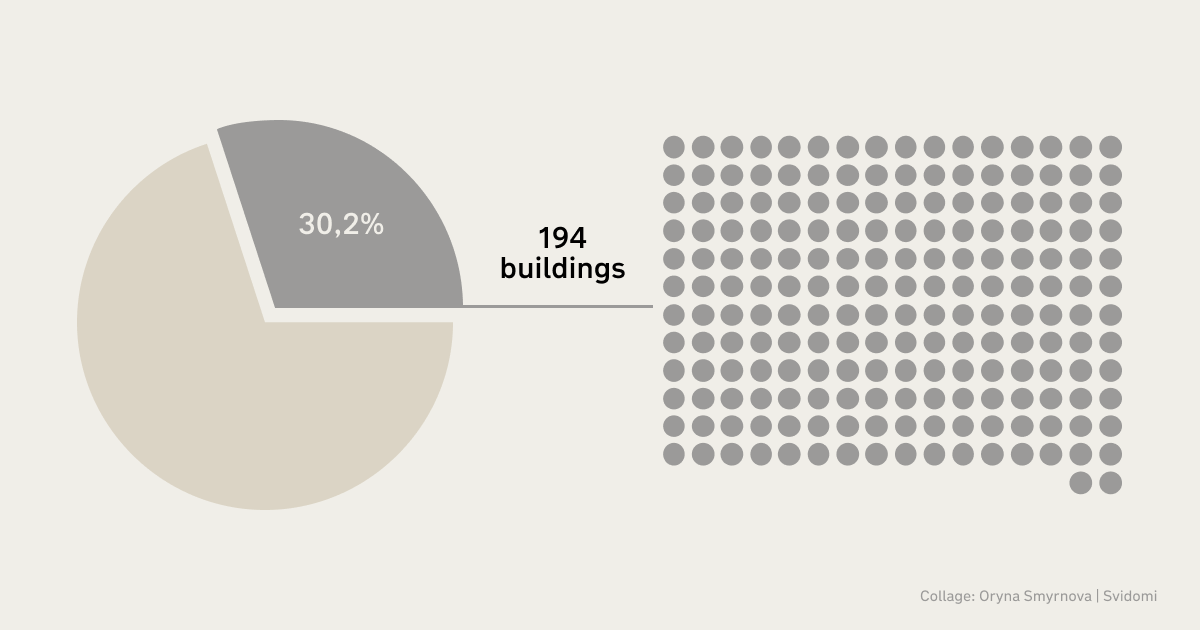

According to the order of the head of the Kherson region state administration [then Andrii Putilov — ed.], as of November 18, 2014, 194 buildings in the region were inventoried, which is 30.2% of their total number.

In addition, roadblocks were erected on the left bank of the Kherson region, and the water supply through the North Crimean Canal was cut off. The former official recalls that the large-scale arrangement of the administrative border with Crimea began a year after the peninsula's occupation.

Oleksii Chachibaia, the former head of the Beryslav District Administration, also recalls the development of an emergency alert system in the city and district, as well as military-patriotic education in schools.

National and patriotic education of the youth

"In Ukraine, schools are government-run (the Ministry of Education is in charge of the development of education content, and schools are financed by the State budget). Accordingly, state executive bodies received orders and implemented them through district education departments," Chachibaia tells Svidomi.

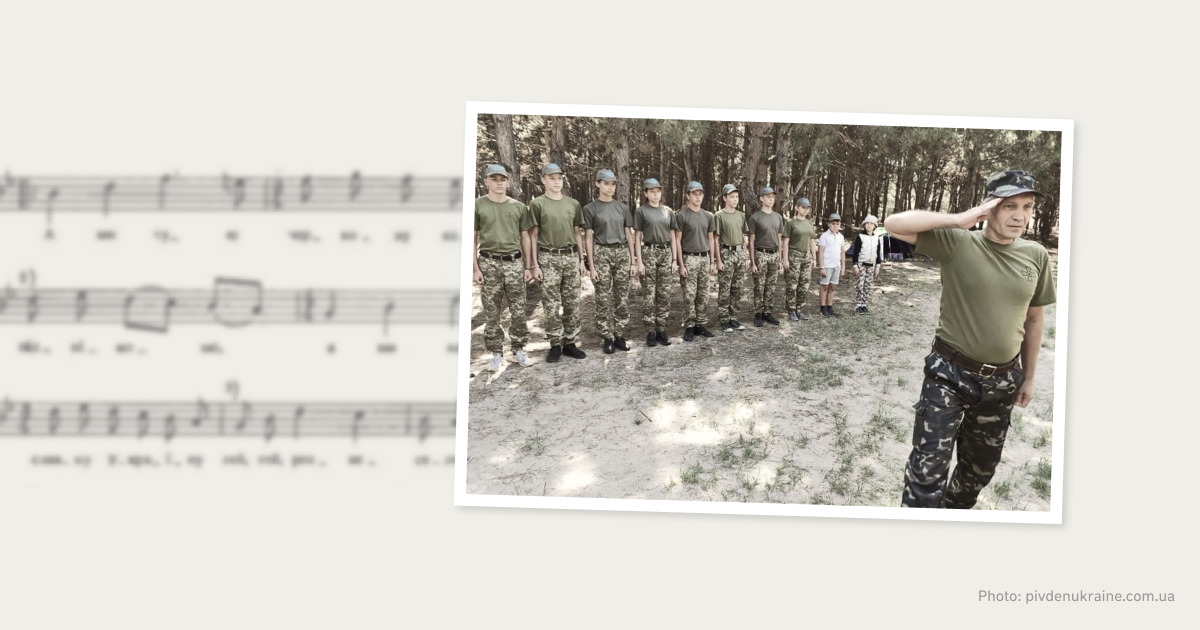

After 2014, the military-patriotic game Dzhura, originally introduced in 2009, gained popularity in Ukraine, including the Kherson region.

The game was included in the 2016-2020 Strategy for the National Patriotic Education of Children and Youth, which was approved by the President in October 2015.

Sokil (Dzhura) is aimed at military-sports and national-patriotic education of Ukrainian youth based on the traditions of the Ukrainian Cossacks. The game is open to children aged 6-10, who are called novaky (newcomers), 15-17, who are called young Cossacks, and 11-14, who are called dzhura.

Olena (name changed for security reasons — ed.), 21, who was born and studied in the Kherson region, believes that the game's launch and growing popularity are directly related to the military and political processes taking place in Ukraine.

"This contest had a great impact on me personally. Patriotic education, chants, Cossack songs and lectures on history motivated me to be more interested," she says.

She also recalls her trips to Nova Kakhovka (which has been occupied since February 24, 2022—ed.) to attend a camp called Sich.

"It was a hyper version of Dzhura. We camped in the forest for a week four times a year. One day, Cossacks would come and hold competitions and give lectures on history. They taught us how to fight. They instilled in us a love for everything Ukrainian," she recalls.

Olena believes that Dzhura increased the number of teenagers who wanted to connect their lives with the military or state defence in the future.

Out of 15, she says, five boys from her group are now serving in the Ukrainian army.

"Dzhura was an incredibly correct and competent decision at that time. I have great respect for those who came up with it and developed it," says Olena.

Military training and formation of the territorial defence brigade

In June 2014, the Defence Council was established in the Kherson region, headed by Yurii Odarchenko, the then-head of the regional state administration.

In addition, in July of the same year, the Kherson Regional State Administration created a commission to check whether the structural units of the regional state administration, district state administrations and city executive committees were ready for mobilization.

The heads of local governments were instructed to inform and prepare the population for partial mobilization. They should be informed about the benefits provided for those called up for military service during mobilization.

The former head of the Beryslav District State Administration (DSA), Oleksii Chacibaiia, adds that the task was to form units of 150 people in each district for territorial defence.

We made these lists, and I, as the head of the DSA, saw to it that our people were taken to the training grounds for combat training. There were also representatives of the Armed Forces, the Military Recruitment Office and instructors,

Chachibaia told Svidomi.

The 123rd Independent Brigade of the Territorial Defense Forces was formed in 2018. The first training camp was held from September 3 to 12 of the same year. Training was held again in December 2018 and off-schedule in April 2021.

In January 2022, a month before the full-scale war, the brigade was assigned to a military unit.

In February 2022, the unit took part in the battles for the Antonivskyi Bridge and the city of Kherson.

The ‘perfect’ plan to prepare for a possible escalation after 2014

"On February 24, 2022, reality showed that what we had been preparing for since 2014 did not work, neither in Kherson, nor in Zaporizhia, nor in Kharkiv, nor in Chernihiv," says Oleksii Chachibaia, former DSA head.

At the same time, he says, the local executive authorities had "clear instructions" on how to act in the event of an offensive after 2014.

Territorial defence units were created, which at the beginning of the invasion were supposed to be armed and guard the region's borders. But the rules implemented in 2014 did not work,

Chachibaia said.

The former head of the Beryslav DSA adds that the nearest civil defence garrison was supposed to be on the left bank (occupied since February 2022 — ed.) of the Kherson region, but at the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion, these territories were occupied by Russians as early as 7 a.m.

Chachibaia adds that all garrisons for territorial defence should have been created in larger numbers, with more people on duty. In addition, Chachibaia notes problems with the time it took to deliver weapons to local territorial defence units. The former chief adds that the weapons should have been on the ground, in warehouses.

Journalist Ivan Antypenko adds that Ukrainian information policy at the state level was weak.

Very, very weak. If you remember from 2014 or 2015, our efforts to ensure the broadcast of Ukrainian channels and radio in the occupied territories were insufficient. Instead, in Kalanchak and Chaplynka (southern Kherson region — ed.), you could listen to Russian radio in your car,

Antypenko concludes.

Echoes of 2014 in 2022, the year of Russia's full-scale invasion

The Kherson journalist recalls that in 2014 the public sector became more active, and it was not just members of non-governmental organizations.

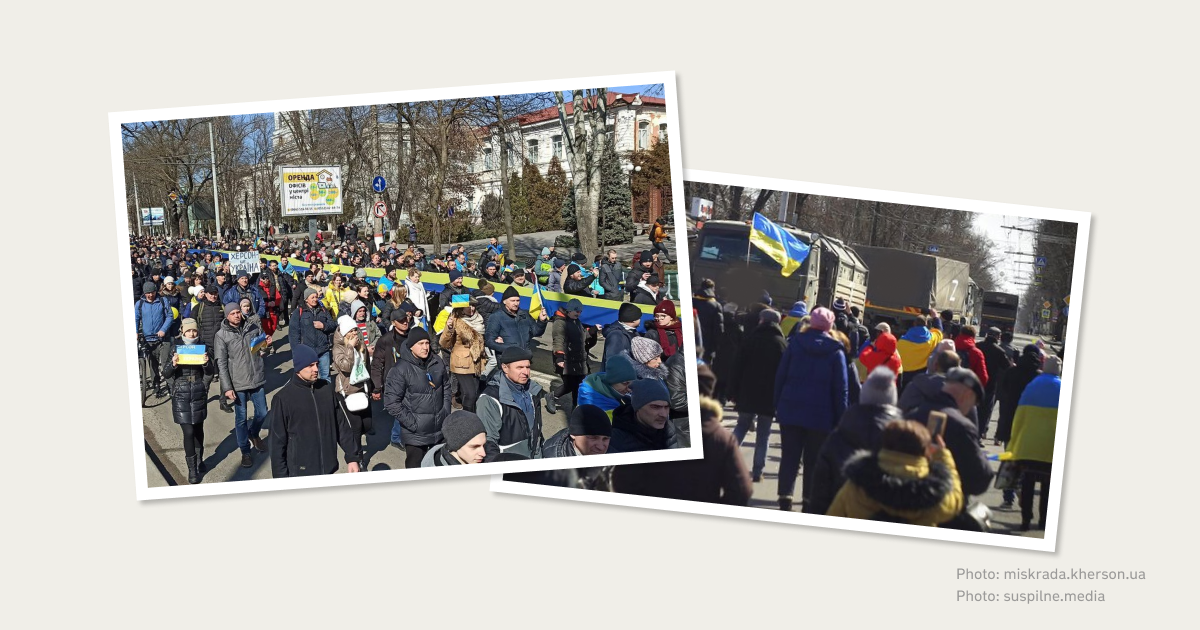

"These were just people who came to the Maidan in November 2013, and when the war broke out in the east in Crimea, some of them joined volunteer units, and some of them helped these units. Civilians did not allow pro-Russian separatist movements to take place in Kherson," Ivan Antypenko said in a comment to Svidomi.

In 2014, separatist movements attempted to hold protests in Kherson in support of Russia but faced local resistance.

In 2022, Russia was also unable to gather a significant crowd that would show that Kherson allegedly supports Russia in large numbers. According to a journalist from Kherson, they failed.

"The real referendum took place in March 2022, not what the Russians drew in September of that year. People who had never been involved in the movements came out en masse with Ukrainian flags," Antypenko says.

He emphasizes that from March to November 2022, many activists, government officials, self-government representatives and civil servants fled the occupation. However, on November 11, the day of the liberation of the right bank of the Kherson region, thousands of people welcomed the Armed Forces of Ukraine again.